Welcome

Welcome to Culpeper Battlefield Tours

Premier Tour Provider of Historic Tours in Culpeper, VA

Premier Tour Provider of Historic Tours in Culpeper, VA

Culpeper Battlefield Tours now offers scheduled tours of Brandy Station Battlefield Park conducted by certified battlefield guides. Contact us to book a tour!

Over 1,000 acres of preserved parkland in Culpeper County Virginia owned and protected by the American Battlefield Trust. Brandy Station is within easy driving distance from Washington, DC and Richmond, VA and is 2 hours from Gettysburg, PA

We offer walking tours, car or bus tours and guided horseback tours of Brandy Station Battlefield Park, which will include stops at Fleetwood Hill, Buford's Knoll and St. James Church. Specialty tours and custom tours are available.

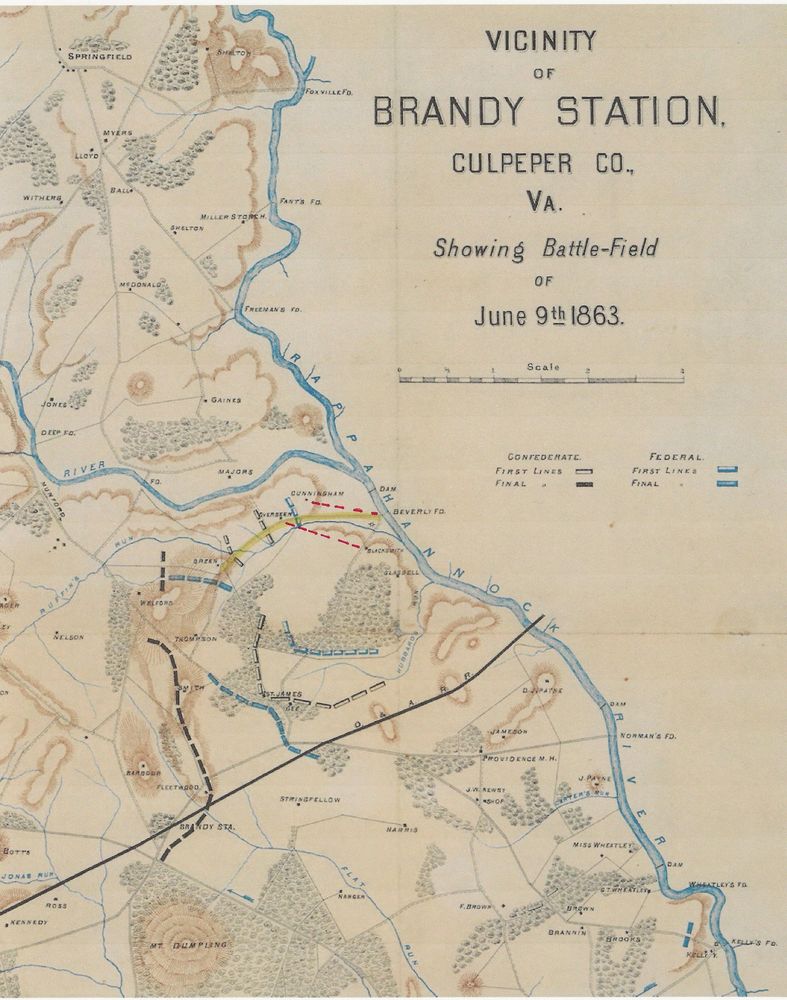

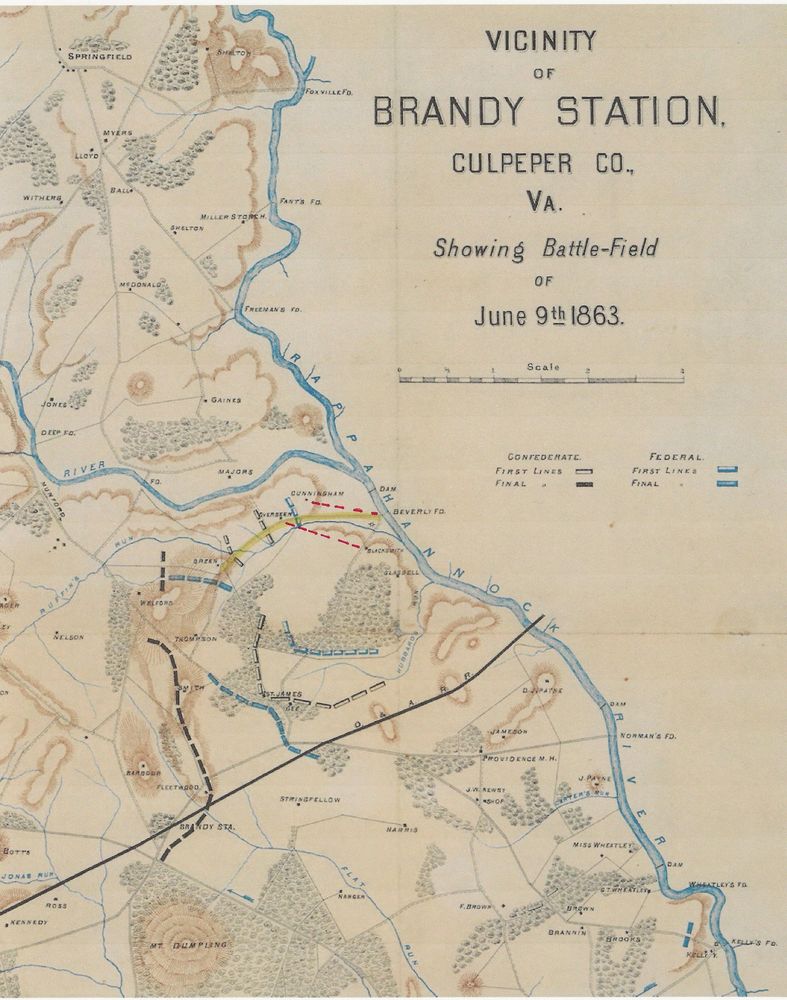

The Battle of Brandy Station on June 9, 1863 was the largest cavalry battle of the American Civil War. The battle was momentous not only in the significance of its historical players, but also to the outcome of the turning-point campaign of the Civil War: Gettysburg.

On June 9, 1863, the largest cavalry battle of the American Civil War took place in eastern Culpeper County, Virginia, near Brandy Station. Never before or after did so many mounted men engage in mortal combat with both modern and classical weaponry in a full display of the mid-nineteenth century’s newest methodologies of cavalry. The fighting was downright vicious across the battlefield but brought out the best and worst in soldiers Union and Confederate as only combat can. The engagement proved the necessity of competent cavalry operations in the warfare then raging across the country.

The battle, like most Civil War battles, was called by several names; Brandy Station, Fleetwood or Fleetwood Hill, and Beverly’s Ford, to name a few. The fight indeed was a turning point in stark contrast for both sides. For the Confederacy, the first two years of the American Civil War offered mostly success with regards to their mounted operations, specifically in the eastern theater. Most contemporary accounts claim this as a result of the agrarian lifestyle of Southern men-of-arms who were much experienced in the equestrian arts long before they ever galloped onto a battlefield. That fact certainly helped, especially when it came to the care of horseflesh and understanding limitations. Another significant influence, though; geography aided these Southern horsemen. They were fighting in their backyard for home and hearth. One Yankee invader who understood this point well, wrote as much to his son saying, “The Rebell Cavalry are fine Riders and Know every inch of ground, and every Cow Path in the Mountain, Which give them a very great advantage.”

Leadership also played a vital role in Confederate fortunes early in the war. Confederate cavalry initially functioned in dispersed units like their Northern counterparts because of the difficulties associated with recruiting and building an army mainly from scratch. However, in September of 1861, Southern cavalry units were formally organized into one cohesive fighting force under the command of General J.E.B. (“Jeb”) Stuart. That initial brigade of cavalry grew into a division of nearly 10,000 men by the summer of 1863. In the Army of Northern Virginia, one hand, Stuart, orchestrated operations in concert with orders from army command. The Federals did not adopt a similar system until early 1863.

Jeb Stuart had proven himself a more than capable commander of cavalry by the summer of 1863. The year before, he twice took hand-selected commands on expeditions that ultimately circumnavigated the entire Army of the Potomac, both raids embarrassing and striking real fear into the Federal high command and the government itself. In battle, Stuart was just as conspicuous and known for his poise under fire. To be sure, there were also close calls along the way, but such defines the character of the best cavaliers, straddling that fence line between rashness and brilliance.

More than anything, General Robert E. Lee valued Stuart’s skillset arguably more than anyone else in the army. Stuart was an idol of the southern citizenry, a true hero in the eastern theater of operations when the situation elsewhere foreshadowed a bleak outcome for the Confederacy. His cadre of subordinates was no-less experienced, and after many shared toils were, for the most part, entirely devoted to the leadership, Stuart dispensed.

The contrast in Union organization and leadership kept northern cavalrymen from any major successes before 1863. Indeed, in hindsight, many rising stars were wearing a blue uniform, but the antiquated system had not caught up to their abilities. It was a long, costly, and painful transition for Federal mounted forces. Command upheavals in the Army of the Potomac specifically hindered progress but, to a degree, fostered opportunities for change. Each new commander took the helm with individual experiences and ideas, some offering more ingenuity than others. It wasn’t until Major General Joseph Hooker took command of the army at the end of January 1863, that a formal cavalry corps would soon be established.

Major General George Stoneman commanding the newly organized corp of cavalry quickly set about recalling the many horsemen that had been distributed among the army’s infantry.

The first notable boost to morale for Yankee horsemen came on Saint Patrick’s Day, 1863. General William Averell led nearly 3,000 horsemen across the Rappahannock River at Kelly’s Ford to strike back at his old West Point classmate, Fitzhugh Lee, for some taunting during a Confederate raid in February.

The affair was spirited, and the Yankees forced a crossing after several attempts. They then deployed and drove Lee’s men several miles away from the ford. Jeb Stuart was in nearby Culpeper Court House and personally responded to news of the breach by riding to the guns and directing his troopers. In the end, Averell deemed it prudent to withdraw his men to the north side of the river, but they had offered a good lick. More than 200 men became casualties that day between both parties. Most notably for the Confederates though, the young and gallant artillerist, Major John Pelham, was hit in the head by a shell fragment and died within hours.

The Federal cavalry’s new-found organizational cohesion was more boldly tested in a somewhat surprising manner when General Stoneman led the majority of the new corps on a raid towards Richmond, while Hooker and the infantry engaged in a flanking maneuver that culminated in the battle of Chancellorsville. Stoneman’s raid was ineffective at best and a complete drain of resources at worst. Promising at the start, after a brief stint indeed, the outcome of the operation led to Stoneman’s transfer from the field to the Washington defenses.

Meanwhile, at Chancellorsville, General Robert E. Lee divided his outnumbered forces in the face of the enemy. He unleashed Stonewall Jackson on May 2 to deliver a crushing blow to the Union right flank, which routed an entire Federal corps. The fighting abilities of Hooker’s men alone saved the army, but even after reforming and fighting tooth and nail the following day, a stunned Hooker ordered his army back across the Rappahannock River.

The few Union cavalry regiments that served with Hooker’s infantry acquitted themselves well in what turned out to be a disaster from May 1-3 in the woods around Chancellorsville. These regiments were all under the watchful eye, or so he claimed, of General Alfred Pleasonton. Proximity to Hooker’s headquarters, which was not accidental, certainly did not hurt Pleasonton’s future amid the fallout after the battle. In the wake of Stoneman’s departure, Pleasonton’s star was rising. Highly ambitious with sometimes questionable motives, he rose to command of the cavalry corps at a critical moment in the history of the army.

While the two massive armies licked their wounds after suffering a combined loss of more than 30,000 men at Chancellorsville, there were important questions to answer in both commands. On one side, the Union cavalry was in transition and still looking to prove their value, now seemingly against all the odds. Stoneman’s raid was a failure, so how would this new organizational system fare on a battlefield? Was success, let alone victory, even attainable?

On the other side, Stuart’s troopers were reliable veterans used to watching the enemy run. Was the inclination for victory sustainable? Would that success breed indiscretion or ultimate victory? The coming campaign would provide all these answers and more. For the cavalry in both armies, all the previous training grounds were pointing to a collision, unlike anyone in either army had ever witnessed before… Brandy Station.

Clark "Bud" Hall

Historian

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.